CHILDREN'S NATIONAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE ACADEMIC ANNUAL REPORT 2021

Spotlight

Clinician scientist sheds new light on an ancient, still-deadly disease

Almost a decade ago, pediatric neurologist Douglas Postels, M.D., suggested that cerebral malaria might express itself differently in different people as a possible explanation for why some patients experienced retinopathy (abnormalities in the back of the eye) and others did not. At the time, this view was so controversial that co-authors on his first publication, which postulated this concept, asked for their names to be removed from the work.

Today, however, he is widely considered to be one of the world’s foremost experts in retinopathy-negative cerebral malaria, largely because he was able to combine his expertise as a clinician and a researcher to re-examine cerebral malaria and how it affects young patients. He shared his journey with Children’s National Hospital faculty and staff during a Grand Rounds presentation in early 2021.

If malaria was not the cause of illness in children with retinopathy-negative cerebral malaria, why were many of these kids getting better after treatment with broad spectrum anti-malarial drugs?" –Douglas Postels, M.D.

The most severe neurological form of malarial infection, cerebral malaria, causes coma. Of the children who fall into coma and are hospitalized for treatment, one out of every six dies. For those who do survive, up to a third have a long-term neurological disability. Two thirds of children diagnosed with cerebral malaria have changes in the back of the eye (retinopathy-positive) but one third do not (retinopathy-negative).

“Across Africa, cerebral malaria is a profoundly important condition to understand and yet there has been no clear reason for why some children respond to treatment and why some don’t,” Dr. Postels said. “It was hypothesized, and in fact assumed, that one quarter to one third of children with clinical cerebral malaria, those who lacked retinopathy, did not have malaria responsible for their current illness.”

The reason? Community-based cross-sectional studies of rates of asymptomatic parasitemia in Malawian children showed this was extremely common in school-aged children. In places of the world like Malawi, where he conducts his research, children are exposed to malaria parasites so often that they stop having symptoms even when the parasite circulates in their blood. Their blood smear may be positive for the parasite’s presence, but something other than malaria may be making these children acutely ill.

The prevailing way to identify if a child’s coma was caused by malaria infection is by looking into the child’s eyes for a common sign of cerebral malaria —retinopathy. If retinal whitening or hemorrhages are seen on a quick eye scan, it is assumed that the child’s coma is caused by malaria. If no retinopathy is seen, it was, until recently, widely assumed that something else, a viral infection or other culprit, might be causing the child’s coma, even if the child also happened to have malaria parasites in their blood.

Dr. Postels had many questions. “I was puzzled. If it was not malaria, what was causing coma in children with retinopathy-negative cerebral malaria? If malaria was really not the cause of their illness, why were many of these kids getting better after treatment with broad spectrum anti-malarial drugs?”

Postels and the team at the Blantyre Malaria Project tried to figure out whether malaria was causing illness in children who were retinopathy-negative using clinical observation and epidemiological studies. But no matter what data they collected and analyzed — seasonality of retinopathy-positive vs. retinopathy-negative disease, or even MRI images from both retinopathy-negative and positive cases — the data told conflicting stories.

“Observational and epidemiological studies weren’t giving us the answers,” he remembered. “We needed to go directly to the source by studying these patients in a clinical setting.”

They started coordinating clinical research across three countries with high rates of malarial infections — Ghana, Uganda and Malawi — to attempt to identify what was causing comas in children with retinopathy-negative cerebral malaria.

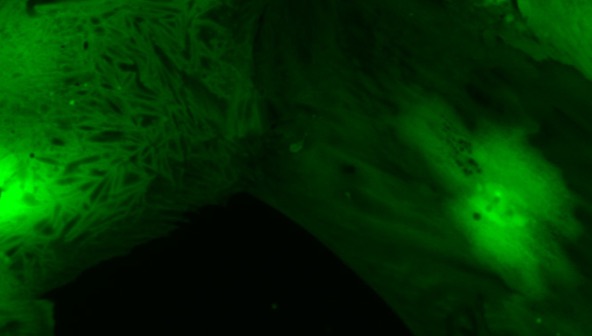

Together through a series of studies, the teams gained a clearer picture. They were able to rule out viral co-infections of the brain as the cause of coma, finding that these viral infections weren’t clinically important in children with retinopathy-negative cerebral malaria. They applied complex mathematical disease models and gathered in-depth information from enhanced optical coherence tomography scans of the patients’ eyes.

It turned out that many of the children diagnosed with retinopathy-negative cerebral malaria, when evaluated using more sensitive optical imaging methods, did have retinal abnormalities. The clinicians caring for the patients simply could not see these changes in the eye using standard instruments. Retinal changes were present but not visible. Complex mathematical modeling yielded the same result: In the vast majority of children with retinopathy-negative cerebral malaria, the malaria parasite was causing the child’s acute illness.

“These studies lent support to the assertion that, in fact, these children were in coma because of the acute malaria infection despite the lack of retinopathy,” Dr. Postels summarized. “They reinforce the idea that though the underlying coma cause is malaria, something else within the unique makeup of that patient or the parasite infecting them changes the severity of abnormalities in the retina and the disease itself.”

The combination of early observational epidemiological studies and the new clinical data has redefined how doctors believe cerebral malaria behaves. Rather than a dichotomous presentation (retinopathy-positive and retinopathy-negative cerebral malaria are two different diseases), doctors now think of the illness as a continuum. This is a significant shift in thinking about this ancient disease, thanks in large part to studies that were coordinated by Dr. Postels over the course of six years.

And those early collaborators who removed their names from Dr. Postels’ earlier publications? They have come around to this new way of thinking. Scientific thought is an always evolving field. As new evidence is uncovered, thoughts and minds must change alongside.